Ontario Commits to Extending Logging Moratorium around Grassy Narrows First Nation for Additional Decade until 2034

“We wholeheartedly applaud this decision. Our fight for over 20 years has finally paid off, and we are immensely satisfied,”

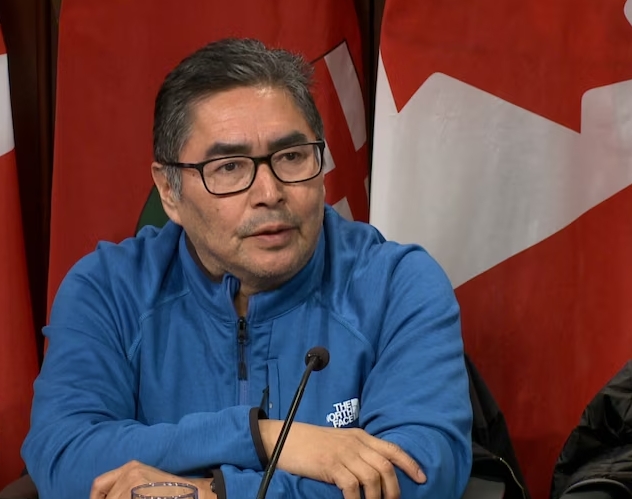

said Joseph Fobister, an activist advocating for the protection of ancestral lands in the Whiskey Jack forest, in response to the announcement.

The logging moratorium, which has been in place since 2017 and was originally set to expire next year, aims to limit industrial activities, particularly clearcutting, in order to safeguard the ancestral lands of Grassy Narrows.

Grassy Narrows has achieved a temporary victory in their ongoing efforts to protect their ancestral lands, with the ultimate goal of securing permanent preservation.

In a letter sent to the First Nation in early February, of which Radio-Canada obtained a copy, the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forests (MRNF) confirmed that no commercial exploitation would be permitted in the protected region. The area of the protected region is identical to that outlined in the previous moratorium.

Fobister also expressed appreciation for the inclusion of First Nation members and leaders in consultations with the province and the development of a new forest management plan for the Whiskey Jack Forest, commencing this month. The MRNF aims to create a comprehensive long-term management plan that includes sustainable harvesting targets.

The job is not done

In a recent communication to Grassy Narrows Chief Rudy Turtle, the MNRF stated its intention to make a decision on the new forest management plan by spring or summer of 2024. Prior to this announcement, the community had sent multiple letters to the MRNF and forestry companies, seeking commitments to refrain from exploiting their territory. In October 2018, the First Nation had declared sovereignty due to concerns that the provincial government would lift the moratorium.

Grassy Narrows has faced ongoing challenges with mercury poisoning among its residents dating back to the 1960s. Multiple studies have demonstrated that logging, specifically clearcutting, contributes to increased mercury contamination in the nearby waterways. Scientific research published in September 2016 revealed that over 90% of the community’s residents exhibit signs of mercury poisoning.

“Over the years, the logging activities have encroached closer to our community and waterways. There are legitimate concerns, supported by scientific studies, that the disturbance of soil during logging could result in increased mercury release into the water,” stated Joseph Fobister, an activist for Grassy Narrows’ ancestral lands.

Grassy Narrows is also advocating for consultation with the Ford government regarding mineral exploration, which has had detrimental impacts, as noted by Fobister. The community’s leaders filed a lawsuit against the province in 2021, challenging the validity of nine permits that were granted without proper consultations.

The chief and several members of the community visited Queen’s Park two weeks ago to voice their concerns about the lack of consultation on mining projects within their territory. This is not the first time they have taken such action, as they also did so in 2014 when they went to the Supreme Court to challenge the province’s jurisdiction over the licensing of industrial natural resources.

The Supreme Court of Canada ultimately ruled that only Ontario could offer land that was ceded by the Ojibways through a treaty in 1873, but the province still has obligations to meet in regards to affected communities.